‘Australia – a land of opportunity?’

It has been about 2 years since I moved to Melbourne from the UK to set up K2 Management’s Australian office. Our move was well timed in that it coincided with the two highest investment years the industry has experienced to date. Since 2016, AUD$27b has been invested in new wind, solar and storage projects, equivalent to some 15GW[1] of new utility scale generation. However, as the bilaterally agreed renewable energy target (RET) has been met and not extended, many have begun to speculate on whether the level of investment will continue.

Many infrastructure investors have a global remit. For example, at any given time, K2 Management may be supporting a single infrastructure investor to simultaneously acquire a portfolio of US wind farms, construct a solar farm in Australia and identify green field sites in Taiwan. So, what is it about the Australian market that has drawn so much interest in recent years and will it be sustained? By comparing my UK and more recent Australian experience, I thought I might offer some insights.

‘Seeking new horizons’

As I was leaving the UK in 2017, the government backed renewable obligation (RO) support mechanism was just ending. Similar schemes existed in many parts of western Europe. The benefit to wind and solar farm owners was designed to reduce over the 15 years of the scheme, reflecting the decrease in costs as the sector matured. But even as it closed, the scheme still provided ~40% of revenue for the first 20 operational years, underpinning the project financial model and helping to secure debt finance.

The primary challenges for UK developers at that time were securing land and planning permission, without being subject to onerous conditions. For infrastructure funds seeking to buy shovel-ready projects, the risks lay in avoiding overly optimistic energy yield predictions and in some countries, determining the extent of grid curtailment as some network areas became congested. Then, around 2015, many European countries, including the UK, shifted from RO or feed-in-tariff schemes to limited volume reverse auctions. Development slowed and, in some countries, halted almost entirely. The trade-off for investors of a relatively de-risked sector, was intense competition for the limited number of available projects and far tighter margins leading to low single digit returns. The European offshore wind sector underwent a similar transition. Suddenly, overseas renewables markets, once considered too difficult, started to look more attractive.

‘Australian abundance’

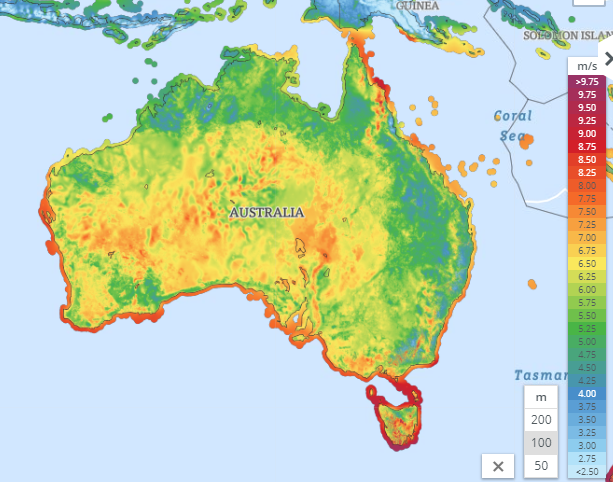

There are many factors that make Australia uniquely suited for renewable deployment. The country is well known for its abundant solar resource but the ‘Roaring 40s’ also provide hub height windspeeds of >7m/s in many states, providing ideal conditions for wind as well as solar projects.

Credit: https://www.globalwindatlas.info/

In relatively densely populated countries like France and the UK, derating or shutting down turbines to avoid the impact of noise and shadow-flicker on nearby residents is not uncommon, in some cases decreasing annual yield by several percent. Australia’s abundant land resource is doubly advantageous in that economies of scale can be achieved by developing large projects, without the need to de-rate to preserve residential amenity. Furthermore, larger, more efficient turbines can be installed because turbine hub heights generally aren’t restricted here as they have been onshore in the UK.

Another key factor that makes Australia attractive to renewable investors is the value of the wholesale electricity market. The table below, comparing the supply capacity and value of the UK and Australian wholesale markets, indicates the size of the opportunity for generation asset owners.

| Metric | Australia | GB |

| Supply capacity | 54 GW | 103 GW |

| Market value | $16.6bn | $6.1bn |

Table comparing market sizes and value (courtesy of https://www.cornwall-insight.com).

If we also consider the expected decommissioning rate of aging coal plants in the coming years and State-led renewable electricity targets, it is little surprise that investors from Europe, US, China and Japan have all turned their attention to the Australian market.

| Region | VIC | QLD | TAS | SA | NEM in 2018 |

| Renewable contribution | 40% by 2025 | 50% by 2030 | 100% by 2022 | 100% by 2030 | ~20% |

Table showing renewable penetration targets by State and current penetration in the NEM.

‘Challenges unique to Australia’

Despite the many advantages it offers, as with every market, Australia has its challenges. In supporting developers and investors to initiate, construct and operate approximately 8GW of wind solar and storage projects in Australia, K2 Management has had first-hand experience of the risks faced by our clients. Marginal Loss Factors (MLFs), grid connection costs, grid code compliance, commissioning delays, securing offtake and various other technical risks all need to be addressed by investors seeking acceptable returns on renewable energy assets in this market.

‘Getting connected’

Described by some global investors as the toughest grid regime they’ve experienced, getting renewable energy projects connected is currently an onerous and uncertain process. The energy transition has produced a number of well documented issues such as annual MLF changes and the opaque grid connection process. Other recent headlines such as the imposition of export constraint on operational solar farms on the border of Victoria and New South Wales raise additional questions.

Credit: AEMO draft MLF cover image

At 40,000km in length, Australia’s eastern transmission network is one of the world’s longest. Marginal Loss Factors (MLF) reflect power lost in transporting energy from the point of generation to the point of consumption and are recalculated annually. The draft Marginal Loss Factors report was published shortly before the federal election and arguably caused greater industry frustration than the Federal Coalition’s lack of climate change policy. Seemingly unpredictable variations of as much as 20% from year to year, are unique to the Australian market and constitute a material risk to project owners.

Similarly, the introduction of new modelling requirements by AEMO earlier this year combined with the volume of applications, has made getting a connection offer far more costly and time-consuming. There are numerous developers who have secured land and development approval, shortlisted component suppliers and agreed an EPC contract price, only to have to projects stall for up to 6 months while they await the findings of Final Impact Assessments (FIAs).

Simply put, FIAs are required for most new large-scale projects to predict how the network may be affected under a range of operational scenarios. The model inputs include, amongst other things, the technical characteristics of the wind turbine or solar farm inverter and an up to date simulation of the network. With inverters and wind turbine controllers constantly evolving, OEM technical teams often being based in Europe, the grid constantly changing as new generators connect and a current shortage of skilled resource to run the modelling, delays of up to 6 months are commonplace. Unfortunately, that’s enough time to lose a pre-agreed module price and manufacturing slot, which then requires another round of EPC price negotiation and may require a reworking of the whole project financial model. Similarly, if the FIA calls for a synchronous condenser or other auxiliary equipment, the project financials may be fundamentally altered. In other global markets such network infrastructure costs are often shared amongst all project beneficiaries or recouped later by the NSP, but in Australia they are typically borne by a single generator.

‘Securing an off-taker’

While grid issues seemingly remain the biggest impediment to the transition to renewables in Australia, developers and investors face other hurdles. Signing up a corporate off-taker is essential to securing traditional project finance but with more projects than off-takers, tenders are often competitive, forcing downward pricing pressure. In addition, getting the first corporate power purchase agreements (cPPA) has been slow and involved, as legal, commercial and contractual norms were established.

Having undergone a lot of learning in recent years however, Australia is now seen as a world leader in this area. The volume of generation underpinned by cPPAs here is greater than in many other global markets and, as other regions seek to adopt the cPPA model in their journey to subsidy-free renewables, they look to Australia for inspiration.

The main drivers of corporate power purchase agreements (cPPAs) are often the need to reduce exposure to high, volatile energy prices and to achieve Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) goals. Despite the addition of many GWs of renewable energy to the grid in recent years, capacity shortfalls at peak demand periods are expected to continue as coal generation is taken offline. Continued strong demand for cPPAs is therefore expected by corporates seeking to hedge against exposure to National Electricity Market (NEM) wholesale market prices. See K2M’s recent report for a global perspective on the emergence of cPPAs.

‘Technical considerations’

Several technical risks have also arisen at various wind and solar construction projects in recent years. To explain how these have materialised, it is worth considering that in 2016, Australia had only a handful of utility scale solar farms. Soon, 9GW[1] of utility scale solar capacity will have been connected. The solar industry, in particular, has undergone considerable learning in that time.

In Queensland, EPC costs on some projects spiralled when unexpectedly tough ground conditions required thousands of piles to be pre-drilled rather than driven. As well as impacting costs, such incidents cause delays while designs are amended and agreed, variations negotiated, and drilling equipment sourced.

Driving piles at an Australian solar farm

Adverse weather conditions have also impacted project schedules. In some cases, tropical storms and rain have caused delays to solar farm installation. Extreme heat has also required EPC contractors to seek local council approval to install at night. If night working was not anticipated, retrospective approval must be sought as working hours are often limited to preserve resident’s amenity. Wind projects have also suffered installation delays as cranes are inoperable in high wind conditions.

Recent phenomenal growth in wind and solar deployment has attracted many new domestic and overseas entrants to the Australian EPC market, driving competition for solar construction contracts in particular. As well as getting value for money, project owners want assurance that the shortlisted contractor has the financial strength, experience and local capability to deliver the project. In undertaking project due diligence, it is not enough just to ensure that risk is appropriately allocated between Principal and Contractor and that liquidated damages caps are adequately sized. Extensive additional checks are needed to ensure the EPC contractor is sufficiently experienced to anticipate project risks and that they are fully priced in the offer. Successful projects are usually delivered by experienced teams comprising personnel from the developer and EPC contractor, often combined with a strong owner’s engineer to manage risks and ensure the project technical specification is met.

‘Equipment bankability’

Another factor of the Australian market is the deployment of new technology. Wind developers seek to increase returns by installing larger rotor turbines at ever higher hub heights. Similarly, new inverter, tracker and module suppliers have flocked to Australia with the aim of winning large solar contracts. Lenders and investors quite reasonably want to know whether new inverters and turbines can pass AEMO’s stringent compliance testing, that tracker systems are designed for the expected wind and soil conditions and whether double glass bifacial modules will achieve predicted yields and degradation rates.

Credit: https://soltec.com/ (Image of a bifacial solar project)

In recent years some investors have suffered from wind farms not achieving their predicted energy yields. In some cases, the cause can be identified and rectified, such as incorrect controller or instrumentation set up. In other instances, recovering overpredicted turbine performance is not possible. This has been the case on projects where layouts, originally approved prior to the 2012-16 hiatus and therefore intended for smaller turbines, are now being built out with contemporary larger rotor machines. Tightly packed layouts can compromise turbine performance, leading to reduced energy yield. Energy yield prediction of Australian solar projects requires similar careful consideration given their unique combination of size, climatic conditions and cutting-edge technology. Consultancies like K2 Management rely on performance data from operational wind and solar projects to inform and validate preconstruction energy yield prediction methodology.

Image showing neighbouring wind turbine effects

‘Challenges and opportunities’

Undoubtedly Australia presents investors with a unique set of challenges that, when considered alongside the current lack of federal policy, are unsurprisingly leading some to assess their regional strategies. However, in the absence of federal support, States are taking the necessary steps to meet their own energy needs and therefore growth in renewables in Australia seems set to continue. The industry has suffered some setbacks in recent years, but it has also learned some valuable lessons.

A number of factors including high electricity pricing, abundant resource, large project sizes and cost efficiencies mean Australian renewable projects can achieve double the returns available in other markets. While clear federal policy would undoubtedly lend greater certainty, none the less, Australia offers well advised investors attractive opportunities and is likely to remain a strong investment market for the foreseeable future.

[1] https://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/resources/project-tracker

About our Guest Author

| Maria is director of K2 Management Australia, a technical consultancy specialising in on-shore and offshore wind, solar and storage advisory and project management. Prior to her arrival in Melbourne to launch the Australian business, Maria was director of the UK subsidiary where she lead the technical advisory and solar functions, undertaking and co-ordinating comprehensive technical due diligence of onshore and offshore wind and solar farm projects globally. Prior to that she held senior management positions at BOC and BP, and consequently has a wealth of project management and plant O&M experience across a number of sectors.

You can find Maria on LinkedIn here. |

I am mystified by the AEMO requirement for synchronous condensers at new PV and Wind sites. All of these new sites use inverters to couple to the grid and inverters can generate VARs or absorb them just as effectively as synchronous condensers. In any case the overall power factor of the grid used to be set by the network not the generator